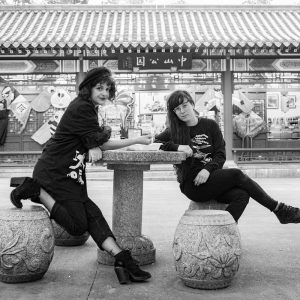

What if making music was a privilege that had to be exploited? La Fièvre, a duo composed of Ma-Au Leclerc and Zéa Beaulieu-April has accepted that mandate, and turned it into a mantra. These modern witches have embraced post-punk, injecting it with their environmental and feminist concerns, while mastering all that electro has to offer – and taken it all the way to the semi-finals of the Francouvertes last fall. Their first, and self-titled, album, released on Oct. 30, 2020, invites us to realize everything that’s collapsing around us.

“The over-arching idea behind our album is really a feeling that we have to do better,” says Beaulieu-April, the voice of the duo. The ecological crisis, and the hardships that particularly affect women, stand as pillars in their songs – which are not exactly weapons, but rather the means of shouting down, and getting out, everything that’s no longer right.

“The over-arching idea behind our album is really a feeling that we have to do better,” says Beaulieu-April, the voice of the duo. The ecological crisis, and the hardships that particularly affect women, stand as pillars in their songs – which are not exactly weapons, but rather the means of shouting down, and getting out, everything that’s no longer right.

“We’re trying to re-connect with a sense of community that’s been lost during the pandemic,” continues the songwriter. “LGBTQ people who find their strength together in celebrating Pride, women who stand up against sexual violence, people who campaign for the environment… All those who depend on their clan, and who have something to lose or defend at this time, are hurt by the isolation due to the pandemic.” There’s a call to action in the music of La Fièvre: an invitation to find oneself, and step out of one’s comfort zone as well. “It’s even more noticeable a song like ‘La crise,’ says Beaulieu-April, “because it says that if you want change, you have to touch the others to keep moving forward.”

The message carried by the two women is as true in their music as it is in their musical journey: You’re not going to get rid of us. “You don’t want us, you don’t want to hear our message, but here we are anyways,” says Beaulieu-April. “We have no intention of stepping aside.”

Ma-Au was classically trained on guitar, and Zéa went everywhere with her djembe (and African hand drum). That’s how their paths crossed when they were in Grade 11. “We decided to do a song about accessibility to drinking water for Secondaire en spectacle and what we did back then was far from electro.,” says Beaulieu-April.

Their current style took hold on an EP released in 2017, and from that point on, their project gelled more seriously. By that point, Ma-Au left the guitar behin,d, and started exploring piano and, naturally, synths. “She started creating all of our sounds. That truly is an art form. I started writing lyrics that were in synch with everything we love, namely pretty enraged electro-pop,” she remembers.

As modern witches, they have a connection with tarot, astrology, and the occult. “We’re very inspired by all that, and there’s an undeniable connection with feminism,” says Beaulieu-April. “Claiming we’re witches is claiming our place among women who were excluded because they were at ease with their healing powers and their sexuality. To us, it goes hand-in-hand with our commitment to eco-feminism. It is really close to who we are and what we do.”

Club music and electro aren’t often associated with political discourse, but the duo insist on reminding us that everything is possible. “We put a lot of effort in researching our sounds. The sounds you hear on the album were all created from scratch by Ma-Au using instruments or programming. They’re sounds created from nothing, and it’s true that to an outsider, it may seem much easier than strumming a guitar. But it’s much, much harder,” says Beaulieu-April.

Everything is malleable in what they do, as Zéa works the themes on one side, and Ma-Au prepares rhythms at home. Then they meet, and the juncture of sounds and words becomes a manifestation of what might exist if we all united. “I know how to program and Ma-Au knows how to write, so there are a lot of opportunities for sharing in our duo,” says Beaulieu-April.

La Fièvre is convinced that having a sense of community has never been more important than it is today, and the fact that music venues have been shut down for several months means messages are no longer circulating. “Initially, we’d planned to launch our album in a swingers’ club last May,” says Beaulieu-April. “We thought it would be cool to meet people we don’t know, to listen to people we never hear about. We spent everything we had, and then some, to bring this album into the world, and then we were faced with an impasse.”

Music that tries to live online has its limitations and, for Beaulieu-April: “It’s artificial, fast, and it feels incomplete So let’s cross our fingers, and reclaim the expression that now stands at the heart of the music industry as a challenge, a threat, or a hope: We have to re-invent ourselves.”