The Canadian Liberal minority government has promised to re-introduce legislation to reform the Broadcasting Act within the first 100 days of being re-elected.

A stated objective is to ensure “foreign web giants” contribute to the creation and promotion of Canadian stories and music. Put another way, the government is looking to even the playing field between traditional and digital media.

You may be wondering a few things from that statement. First, why do we need regulations to “even the playing field,” and second, why did the previous efforts to update and revitalize the Broadcasting Act not succeed?

The Need for Digital Canadian Content Rules

In 1971, the Government of Canada recognized a problem: Canadian music wasn’t being played on Canadian radio, but foreign artists (mostly American) were.

This meant that non-Canadian artists received the vast majority of radio airtime. Money flowed from Canada to support foreign talent rather than our Canadian talent.

As a result, Canadian Content (“CanCon”) rules were implemented for radio stations. The CanCon rules require that at least 35 percent of music broadcast by radio stations during peak hours must meet a defined minimum level of “Canadian.” In Québec, the level increases to up to 65 percent for French-language radio stations. The rest of the “traditional” sector (television and cable) also has its own CanCon rules.

Those rules have been enormously successful in ensuring that Canada has its own cultural industry and Canadian voices, creating, sustaining, and building a significant source of monetary, emotional and cultural value. There are few, if any, aspects of Canadian culture that foster as much national pride and value as the success of music made in Canada.

Today, we’re facing a similar but new challenge: Canadian music isn’t sufficiently prominent on internet-based services.

As digital services become the primary source of music consumption for Canadians, this lack of prominence presents a major issue for Canadian creators.

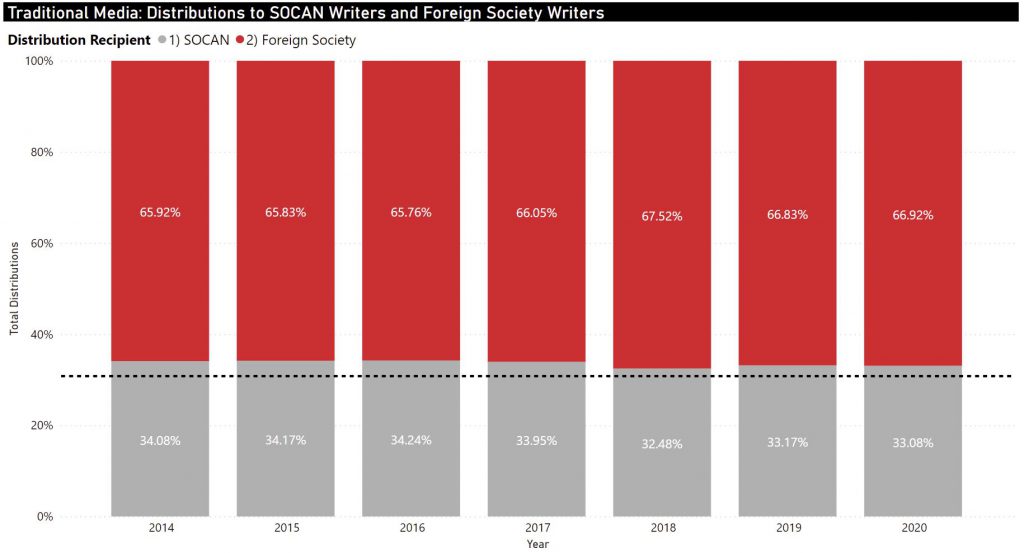

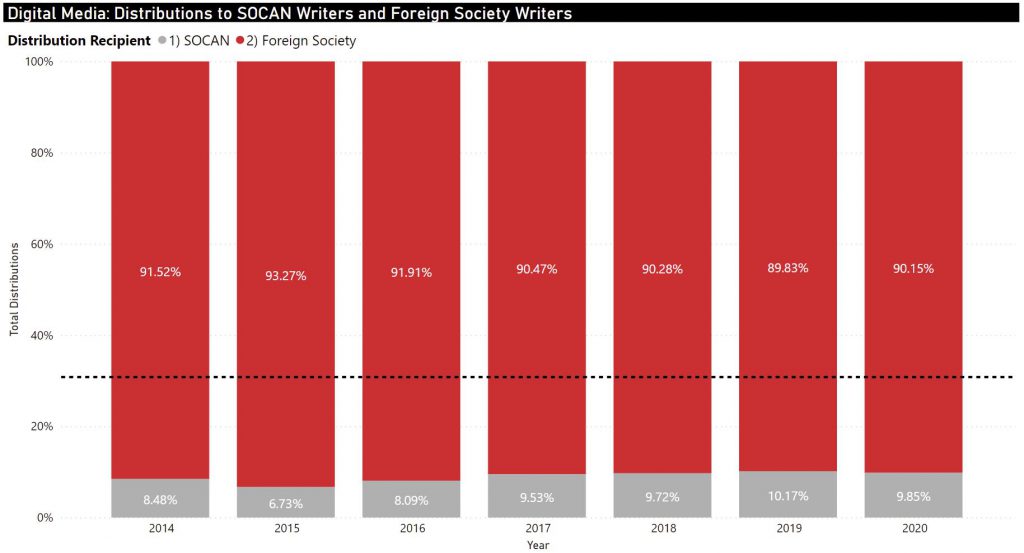

A comparison of SOCAN’s royalty distributions to SOCAN songwriter and composer members demonstrates the disparity between traditional media (radio and TV) and digital media (online music services):

Without modern CanCon rules built for now and the future, we will continue to see a catastrophically unfair decline in the success of Canada’s music makers – from 34 percent of royalties collected on traditional media distributed to SOCAN writer members, to barely 10 percent of royalties distributed to Canadian songwriters and composers through digital media.

The transition from traditional media to digital media continues to increase as more and more Canadians turn to digital services to discover and listen to new music.

So, the question is: How can we safeguard the success of Canada’s creators on digital services?

The answer is to bring the Broadcasting Act into the digital era, to enable the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (the CRTC) to explore rules relating to a modern and fair version of CanCon.

It is impossible simply to transpose traditional CanCon rules to the digital world. That is, to require 35 percent of all content on digital services be Canadian. The digital realm works differently.

Traditional services “push” content to consumers. It’s possible to mandate that some of the content that’s pushed must be Canadian Content.

By contrast, users of digital services “pull” content from those services on-demand. It’s not realistic or even possible to mandate that users pull Canadian Content.

These are complex issues that would become open to review by the CRTC as part of a broader regulatory mandate over digital media services.

The CRTC has shown itself to be an effective administrative means of implementing Canadian cultural policies in traditional media. The organization can continue to play that role in the digital world, now and in the future, as new solutions are crafted.

Bill C-10: The First Attempt to Reform the Broadcasting Act

The previous federal government introduced Bill C-10 to allow the CRTC to regulate online undertakings. However, the initial draft of the bill excluded social media services, which meant that these digital platforms—some of which are the largest and fastest-growing in the world—could escape regulation.

The social media exemption was ultimately removed from the bill, but other amendments were added to state explicitly that users (and the programs they upload) were not being regulated by it. As a result, Bill C-10 targeted the broadcasting activities of the platforms, not Canadians.

Despite this clear exemption, critics of Bill C-10 continued to conflate in the media that the freedom of expression of users was under attack. This controversy ultimately overshadowed what the bill worked to accomplish: to level the playing field between traditional services, which operate under CanCon regulations, and digital media services, which do not.

The controversy around Bill C-10 was an unfortunate distraction from the vital issue: The Broadcasting Act must be reformed for the digital era. For a law that hasn’t been updated since 1991, it’s imperative to continue to sustain and build Canadian-made music, so that we can continue to benefit from this nationally and globally successful industry and source of invaluable cultural pride.

Unfortunately, Bill C-10 ultimately expired on the order paper when the federal election was called in August of 2021, leaving the obvious, necessary and vital addition of digital services to the Broadcasting Act in limbo.

What’s Next?

The newly elected government has confirmed Broadcasting Act reform as one of its top priorities, promising to introduce new legislation in the first 100 days of coming into office.

This will be a watershed moment for Canadian cultural policy.